INTRODUCTION

Accumulating data have demonstrated the importance of sleep in overall well-being. Studies have reported the negative impact of insufficient sleep on psychological health, such as fatigue [1-4], inattention [5-8], forgetfulness [9,10], irritability [11], and depression [12-14]. Moreover, sleep deprivation also affects physical health, resulting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease [15-17]. On the other hand, optimized sleep has been identified to be related to enhanced memory consolidation [18-20] and improved workplace performance [21-23]. Neuroscience research has demonstrated that sleep is important for the elimination of harmful proteins from the brain that may be related to the development of Alzheimer’s disease [24,25]. With the development of modern technology, sleep education has become more accessible to many people. The benefits of adequate sleep have become common knowledge among the general population [26]. Therefore, people are expected to prioritize sleep in their daily life activities. However, according to a survey by the National Sleep Foundation [27] and a national survey in the United States of America [28], the actual hours of sleep do not exhibit an increasing trend but rather a decreasing pattern over the years. Sleep education should be promoted to highlight the importance of sleep [29].

However, the question remains–does sufficient knowledge guarantee the practice of corresponding behaviors? The knowledge-attitude-behavior model [30] considers that knowledge is essential for changes in attitude and behavior and suggests that health-related behaviors could be promoted by providing knowledge through education. However, other models of health-related behavior suggest that an individual’s behavior is not solely influenced by knowledge or cognitive belief, but also by emotional and motivational, social factors along with the economic environment [31,32]. Therefore understanding how important people consider sleep relative to other daily life activities, as well as how they prioritize sleep in behavioral practice is essential. This will provide a direction for the design of sleep education programs.

Therefore, we conducted an online survey to understand how people prioritize their sleep among different daily activities as well as the actions they take when sleep conflicts with other commitments. If these two aspects align, suggesting that the more significance individuals place on sleep, the more likely they prioritize sleep when it conflicts with other activities. Moreover, sleep education should be designed to convey the importance of sleep. However, if an individual’s beliefs regarding the importance of sleep are not consistent with their behavior, then sleep education focusing on the benefits of sleep might have a limited impact. Furthermore, the skills to facilitate individuals’ control over time and behavior might be an essential component in the design of sleep education programs.

METHODS

The participants were recruited via an online survey platform (Survey Monkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA). The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age >18 years and 2) full-time employment. Online informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study. Initially, 914 participants participated in this study. However, 16 participants were excluded from the analyses because of missing data. The final sample included 898 participants (372 males and 526 females) aged 20–68 years (mean: 39.74 years; standard deviation [SD]: 10.04 years).

The survey collected demographic data and three main aspects concerning sleep priorities in attitudes and practices. Demographic data included age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupational level, occupational category, daily working hours, and individual monthly income. First, the participants were asked to answer “How important is sleep to you?” on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “0–not important” to “5–very important.” Second, they were requested to prioritize six life activities–sleeping, work, family activities, leisure activities, social activities, and exercise–based on their importance. Attitude priority scores were derived from the rankings. A score of 6 was assigned if sleep was placed as the priority, 5 if the second priority, 4 if the third priority, 3 if the fourth priority, 2 if the fifth priority, and 1 if the final priority. Third, participants were asked to recall the last time their sleep conflicted with each of the other daily activities listed in the second part and to report the activity they finally prioritized. The sleep priority practice scores were derived from the aforementioned ratings. For each conflicting situation, one point was given if the participant chose to go to sleep, and no point was given if the participant chose another activity. The sum of the points plus one was considered as the priority sleep practice score. Thus, the participant would have a score of 6 if they chose sleep for all conflicting situations and would have a score of 1 if they chose other activities for all items. The discrepancy between attitude and practice scores was calculated by subtracting the attitude score from the practice score.

The chi-square test was used to examine whether differences were identified between priority attitudes and practices. An independent sample t-test was conducted to explore the effect of gender on the priority and discrepancy scores. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences in sleep attitudes, sleep practices, and discrepancies among occupational ranks, occupational categories, and ranges of individual income. Pearson’s correlation was used to explore the association between daily working hours and discrepancy scores. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical committee permission statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the National Cheng-Chi University (Application No. NCCU-REC-201702-I001; Approval Date: 8th February, 2017) and was performed following the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

RESULTS

The descriptive results of demographic information, including sex, marital status, level of education, occupational rank, occupational category, and individual monthly income, are presented in Table 1. The gender ratio between males and females was 1:1.41. The marital status demonstrated that 51.2% of the participants were married and 42.7% were single. Additionally, for educational level, 81.8% of participants had college degrees. The average daily working hours were 8.79 hours (SD=1.69). Furthermore, among the occupational ranks, 61.9% were general staff, 31.9% were managers, and 5.4% were selfemployed workers. The occupational categories were quite diverse, with 14.5% in the medical health industry, 14.3% in the educational service industry, 13.8% in the traditional manufacturing industry, 13.3% in the electronic information industry, and 10.4% in the general service industry. The individual monthly income received by 54.2% was between New Taiwan dollar (NT$) 30,000–59,999, 21.4% received between NT$ 60,000–89,999, and 12% received under NT$ 29,999 or above NT$ 90,000.

Regarding the rating of the importance of sleep, the survey data demonstrated that over 98.3% of the participants prioritized sleep to varying degrees. According to the results, 48.7% of participants (n=437) considered sleep as “extremely important”, 30.2% (n=271) considered sleep as “very important”, and 19.4% (n=174) considered sleep as “important;” however, only 1.8% of the participant considered sleep as “not important” (0.6%, n=5) or “extremely unimportant” (1.2%, n=11).

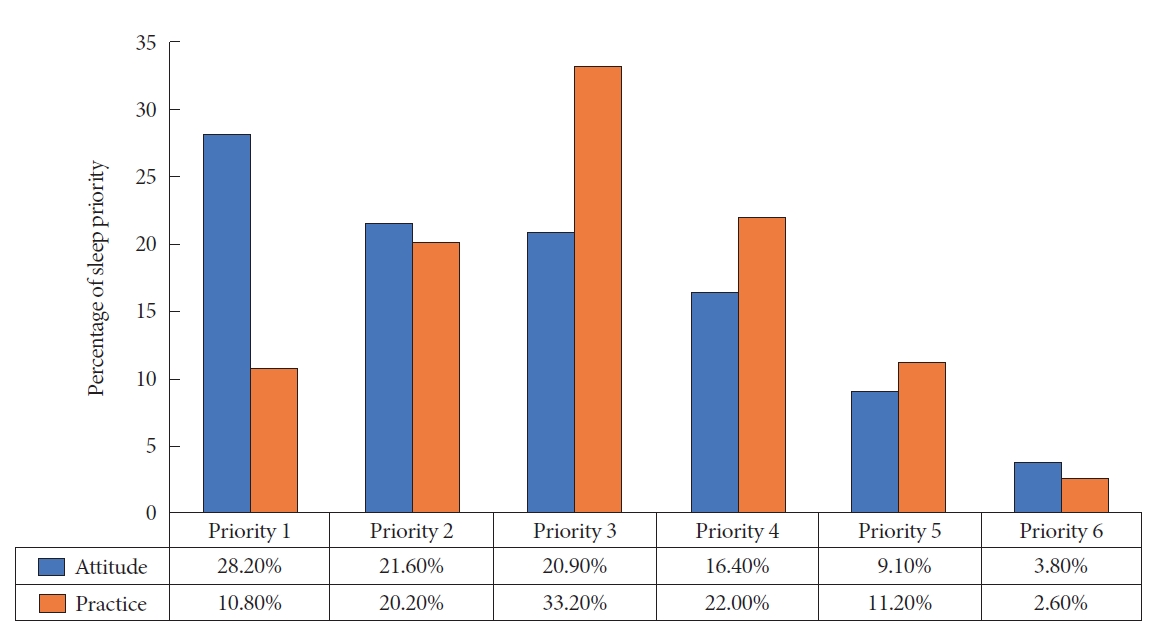

In terms of the participants’ sleep attitude priority, the blue bar presented in Fig. 1 illustrates that 28.2% of the participants prioritized sleep as the first priority, 21.6% as the second, 20.9% as the third, 16.4% as the fourth priority, and 3.8% as the last priority. The orange bar in Fig. 1 represents the participants’ sleep practice priority, with 10.8% (n=97) of participants choosing to go to sleep as the first priority, 20.2% (n=181) as the second, 33.2% (n=298) as the third, 22.0% (n=198) as the fourth, 11.2% (n=101) as the fifth, and 2.6% (n=23) as the last priority.

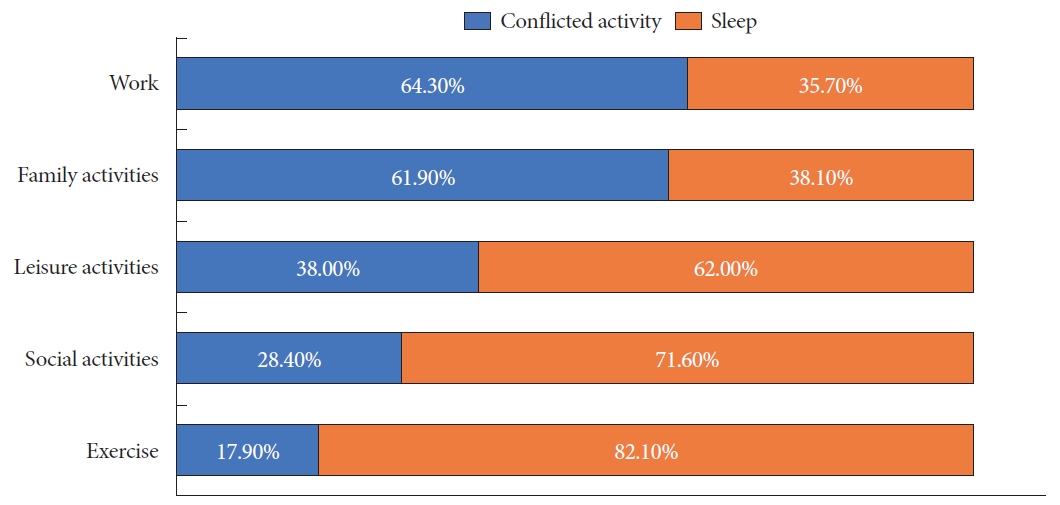

The discrepancy scores between attitude and practice priorities are displayed in Fig. 2. The Chi-Square test exhibited a significant inconsistency between attitude priority and practice priority (χ2=311.755, p<0.001). Only 34.6% (n=311) of participants displayed behavior that was consistent with their sleep attitude; 44.0% (n=395) tended to sacrifice sleep even with high priority for sleep in attitude, 21.4% (n=192) chose to go to sleep even with high ranking for other daily life activities. Regarding the main reasons for the conflicts, our survey identified that 64.3% and 61.9% of participants sacrificed sleep for work and family activities, respectively. A small proportion of participants sacrificed sleep for leisure activities (38.0%), social activities (28.4%), and exercise (17.9%) (Fig. 3).

As for the demographic data, the results (Table 2) demonstrated no significant difference between the sexes in sleep attitude (t=-1.721, p=0.086) and sleep practice priority (t=1.031, p=0.303) but a significant difference in the discrepancy score was observed (t=-2.623, p<0.01). Females choose to sacrifice sleep more than males. In addition, Pearson correlations demonstrated that daily working hours had a modest significant correlation with discrepancy scores (r=0.078, p<0.05), but no significant correlation was observed with sleep attitude (r=0.045, p=0.18) or sleep practice (r=-0.039, p=0.25). Age had a low significant correlation with sleep attitude (r=-0.130, p< 0.01) and discrepancy score (r=-0.155, p<0.01), but no significant correlation with sleep practice (r=0.033, p=0.327). Regarding individual income levels, the results of ANOVA analyses (Table 2) exhibited no significant differences between individuals with different income ranges in terms of sleep attitude, sleep practice, and discrepancy score. Concerning the occupational ranks, a significant difference was observed between different occupational ranks regarding sleep attitude and the discrepancy score. However, no significant difference was present between occupational ranks regarding sleep practice. Post-hoc tests displayed that compared to general staff, middle-level managers and self-employed workers had significantly lower sleep priority attitude scores. General staff and lower-level managers also had significantly higher discrepancy scores compared to middle-level managers and self-employed workers. This implies that general staff and lower-level managers tended to sacrifice more sleep, while middle-level managers and self-employed workers tended to sacrifice less sleep. With regard to occupational categories, the results of the ANOVA tests (Supplementary Fig. 1 in the online-only Data Supplement) exhibited significant differences in sleep attitude (female=1.831, p<0.05) and discrepancy score (female=2.888, p<0.001). Among all occupational categories, workers in the mass media communication industry had high sleep priority attitude scores, whereas workers in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industries, along with the unemployed workers, had low sleep priority attitude scores. However, the discrepancy score demonstrated that mass media communication industry workers had significantly high scores, while the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industries, as well as the accommodation and catering industries, had significantly low scores.

DISCUSSION

As expected, our survey demonstrated that most participants recognized the importance of sleep. When compared with other activities in life, sleep was the top priority for nearly 30% of the participants, meanwhile more than 70% of the participants placed sleep in the top three priorities. However, this endorsement of the importance of sleep in their attitude was not reflected in their sleep practices. Only approximately 37% of participants chose to go to sleep when it conflicted with work or family activities. Although more participants chose to go to sleep when it conflicted with social or leisure activities or exercise, a quarter to a third of the participants sacrificed their sleep for these activities.

These results do not fully support the knowledge-attitudebehavior model, which predicts that attitudes guide people’s behavior. These findings suggest that going to sleep when it conflicts with other activities, is not merely a rational decisionmaking process based on a decisional balance of pros and cons. Several theories have been proposed to explain people’s engagement in health-related behaviors. For example, the health belief model [33] suggests that engagement in health-related behaviors depends not only on the perceived benefits of action but also on perceived barriers to action. Therefore, situational factors, such as social pressures from the job, family, or friends, might impede the intention to go to sleep in light of its perceived benefits. Other theories such as the theory of reasoned action [34] and the theory of planned behavior [35,36] further consider social influence (perceived subjective norms) and self-control (perceived behavioral control). Therefore, the decision to go to sleep is influenced by both social and environmental factors. However, some theories have also focused on motivational and emotional factors. For example, self-regulation theory [37] emphasizes the role of internal desires. According to this theory, attitude is a distal cause of intention, mediated by desire. Therefore, in light of the attitude that sleep is more important, people may still stay awake while performing other desirable activities. These theories explain why sleep is deprioritized in certain situations. Future studies should explore the influences of the aforementioned factors on sleep practices.

Our study also demonstrated an unexpected but interesting finding: 21.4% of the participants chose to go to sleep when it conflicted with other activities, even though they did not rank sleep as a high priority. However, what influences these individuals to prioritize sleep remains unknown. One possibility is that the participants were too sleepful to remain awake for other activities. Moreover, to investigate levels of sleepiness and possible sleep disorders in these individuals in future studies would be interesting.

Further examination of the associations between the participants’ background information and their sleep priorities also provided some insightful findings. All demographic variables collected demonstrated no significant influence on the sleep priority practice score, suggesting that the tendency to sacrifice sleep for other activities is a common phenomenon across different ages, genders, occupations, and socioeconomic levels. However, sleep priority attitudes were discovered to differ among participants of different occupational ranks and categories. Specifically, general staff and lower-level managers prioritized sleep more than middle-level managers and selfemployed workers. Media and communication workers had high sleep priority attitude scores, whereas agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting workers and unemployed participants had low attitude scores.

Individuals with high sleep priority attitude scores also exhibited a high discrepancy between attitude and behavioral practices. Several factors may have contributed to the differences in results. First, age and opportunity to receive sleep education may have played a role. Age displayed a significant negative correlation with sleep priority attitudes and discrepancy scores. As general staff and lower-level managers tend to be young, they may possess a strong awareness of sleep health and therefore value sleep more. Following from that, workers in the media and communication industries might have greater opportunities to be exposed to sleep education information leading to high ratings on the importance of sleep. Conversely, workers in agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting may have limited exposure to sleep education, resulting in a comparatively lower prioritization of sleep. Another possible reason is that general staff, lower-level managers, and media and communications workers may have long or less flexible work schedules. Daily working hours displayed a minor but significant positive correlation (r=0.078) with the discrepancy scores. Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that perceived time control is an important factor in occupational stress [38]. Therefore, low perceived time control in these populations may have led to increased sleep disturbances and concerns about getting sufficient sleep. Another finding of the current study was that female participants had significantly higher discrepancy scores than male participants. Although, female participants did not sacrifice sleep for other activities more than male participants did had a near-significant trend (p=0.87) of higher sleep priority attitude than male participants. The prevalence of insomnia is higher in females than in males [39]. A possibility exists that increased sleep difficulties in females compared to males lead to greater sleep value. A somewhat unexpected negative finding was that individual income level did not have an impact on either the attitude or practice of prioritizing sleep. These results suggest that insufficient practice in getting enough sleep is not simply driven by practical concerns such as financial needs or family burdens, but also by other cognitive, motivational, and emotional factors. The study also highlighted the need to further understand the factors that might impede the practice of healthy sleep habits in different subgroups.

In summary, this study demonstrates that people sacrifice their sleep for other activities in life, especially work and family activities, despite emphasizing the importance of sleep. Although the current study did not assess the reasons why participants chose to sacrifice sleep, the study has important implications. First, although sleep education has become more accessible and is promoted due to the increased recognition of the importance of sleep, most programs focus on knowledge of the mechanism and function of sleep and the pathology of sleep disorders, as well as principles of sleep hygiene practice. Although this understanding could be crucial in encouraging individuals to prioritize sleep over other activities, it is equally essential to offer them strategies to reduce conflicts between sleep and other daily obligations (e.g., time management techniques), deal with social pressure, or resist the urge to continue engaging in other activities when it is time to go to bed. Second, the findings of our study indicate that work and family activities are the two activities for which people tend to sacrifice sleep, and an individual staying awake until a later time due to job demands is understandable. These findings highlight the importance of sleep education in the workplace. A growing body of literature emphasizes the positive influence of sufficient sleep on employees’ work performance, problems at work, and safety issues associated with sleep deprivation [40,41]. Therefore, the promotion of sleep-friendly work policies is required. In addition, studies on the influence of family members on sleep are limited. Future studies are required to investigate the effect of factors, such as family duties and interactions, on an individual’s sleep. Third, the study demonstrated that although insufficient healthy sleep practice was common across all participants, the contributing factors might be different for some subgroups. Further studies are required to explore the specific factors in these subgroups. In addition, sleep education needs to consider the specific factors of the target populations.

Although this study has important implications, the study also has some limitations. First, we conducted an online survey. The sample might have been limited to people familiar with Internet technology. Therefore, the generalizability of our results is limited. Second, sleep practices were measured retrospectively. Recall bias may been incorporated in their report. Future studies using daily recalls should be conducted to confirm our findings. Third, sleep attitudes and practices may be affected by sleep habits and disorders. For example, individuals with insomnia tend to change their sleep schedules, have excessive bed rest, and take more daytime naps. However, our survey did not include questions about sleep habits and sleep disorders; hence, the influence of these factors cannot be ruled out. Finally, our study is more descriptive and demonstrates this discrepancy without exploring the factors underlying the phenomenon. Future research should further explore the influence of individual characteristics and/or social factors, as well as different cognitive and emotional factors, on the priority and practice of sleep.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated an inconsistency between the reported prioritization of sleep and behavioral practices when sleep conflicts with other daily life activities. Although people recognize the importance of sleep and prioritize it over other activities, they tend to sacrifice sleep when it conflicts with work and family activities. The results suggest that sleep education should not only emphasize the importance of sleep but also provide practical solutions when sleep conflicts with other activities. Furthermore, sleep education should be promoted in workplaces to eliminate conflicts between sleep and work demands.