AbstractObjectivesTo investigate the relationship between subjective sleep quality and cognitive function in patients with subjective memory impairment (SMI), a self-perceived cognitive decline without objective cognitive impairment, and amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI).

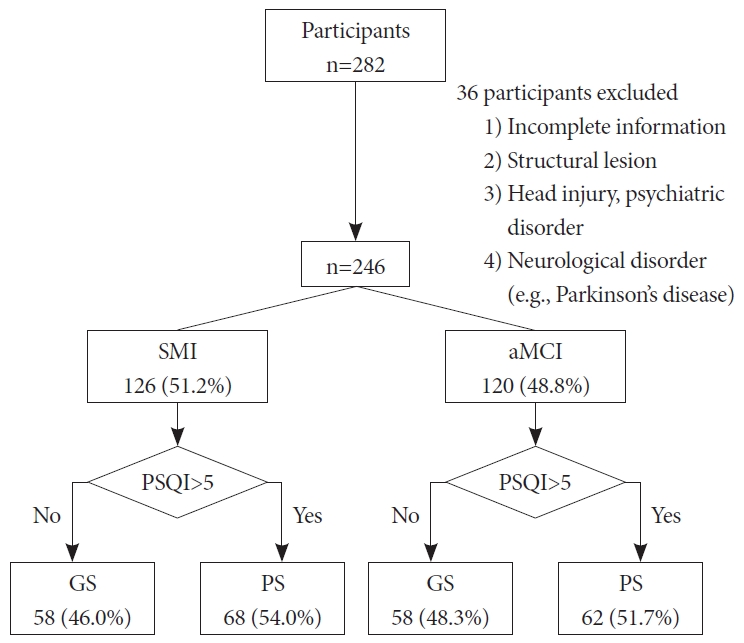

MethodsWe enrolled 246 patients with memory impairment (126 with SMI and 120 with aMCI) who fulfilled the Korean version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-K), a standardized battery of neuropsychological tests, and mood questionnaires. Based on the PSQI-K cutoff point of 5, patients were classified as good sleepers (GS) or poor sleepers (PS).

ResultsThere was no difference in the proportion of GS and PS between patients with SMI and aMCI [68 PS (54.0%) in SMI vs. 62 PS (51.7%) in aMCI, p>0.05]. Demographics did not differ between the SMI and aMCI groups. In both the SMI and aMCI groups, PS had worse sleep-wake parameters, such as sleep latency, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency, than GS and reported worse performance in all PSQI-K subcomponents. Neuropsychological data were not different between GS and PS, except for the Stroop word test in patients with aMCI. Depressive scores were worse in PS than in GS in both the SMI and aMCI groups.

ConclusionsWe observed that cognitive function was not significantly different between GS and PS in both the SMI and aMCI groups, except in the Stroop word test in the aMCI group, while PS had more depressive mood than GS in both groups. This suggests that subjective sleep quality may depend on mood disturbances in patients with mild cognitive impairment.

서 론국제연합은 65세 이상 노인인구 비율이 7%, 14%, 20% 이상이면 각각 고령화사회, 고령사회, 초고령사회로 분류하는데, 국내 65세 이상 인구는 2017년에 13.8%에서 2019년 15.1%로 이미 고령사회로 진입하였고, 2067년에는 고령인구가 46.5%를 차지할 것으로 예측된다[1]. 고령화가 진행되면서 노인의 대표적 질환인 치매도 증가하고 있어 주관적 기억장애(subjective memory impairment, SMI)나 경도 인지장애(mild cognitive impairment, MCI)에 대한 사회적 관심도 증가하고 있다. SMI나 MCI는 일상생활 능력은 유지되나 주관적 혹은 객관적으로 인지기능 저하가 나타나는 상태로 치매 이전의 단계이다[2,3]. MCI는 치매의 전 단계로 알려져 있으며 특히 기억상실형 MCI(amnestic MCI, aMCI)는 기억력 저하를 주 증상으로 나타내며 알쯔하이머병(Alzheimer’s disease, AD)의 중요한 위험인자로 알려져 있다[2-4]. 65세 이상의 일반 인구 집단에서 MCI의 유병률은 3~19% 정도로 보고되는데, 이들 중 약 절반 정도는 5년 안에 치매로 진행하는 것으로 알려져 있다[4]. SMI는 MCI나 AD의 초기 증상으로 치매 발병 수 년에서 수 십년 이전부터 나타날 수 있기 때문에 치매로 진행하기 전 단계인 SMI, MCI 환자들에 대한 조기 발견과 관리가 중요하다[5,6].

유전적 요인, 뇌혈관질환, 당뇨병과 같은 기저질환을 비롯한 다양한 인자들이 SMI, MCI, 및 치매에 영향을 주는 것으로 보고되고 있으며, 그 중 수면장애는 중재 가능한 주요 위험요소로 잘 알려져 있다[3]. 최근 발표된 국내 코호트 연구에서도 입면시간이 길고, 수면시간이 7.95시간보다 긴 노인들에서 그렇지 않은 군에 비해 4년 후 추적조사 결과 인지기능 저하 위험이 1.5배 정도 증가하는 것으로 보고되었다[7].

그러나 기억력 저하를 호소하는 인지기능 저하 환자들은 실제 수면 문제가 있음에도 자신의 문제를 잘 인지하지 못할 가능성이 있다. 객관적으로 수면의 질이 떨어지는 노인층이 건강한 젊은 층에 비해 주관적 수면의 질 점수는 큰 차이가 없는 것으로 보고하고 있으며[8], 주관적인 수면의 질이 인지기능에 어떤 영향을 미치는 지를 조사한 선행연구들에서도 일관된 결과를 보이지 않았다[3,7,9,10]. 이는 인지기능 저하가 주관적 수면의 질 평가에 장애가 될 가능성을 시사하나, 인지기능과 수면의 질과의 관련성을 조사한 연구는 부족하다.

이에 본 연구진은 주관적 기억력 저하를 호소하는 환자들 중 객관적 인지 저하가 없는 SMI 집단과 경미한 인지 저하는 있지만 치매의 이전 단계인 aMCI 집단의 환자들을 수면의 질에 따라, 수면의 질이 좋은 군(good sleeper, GS)과 수면의 질이 나쁜 군(poor sleeper, PS)으로 분류하여 두 군간의 임상 양상의 차이와 인지기능검사상의 차이점을 알아보고자 하였다.

방 법대 상본 연구는 의무기록을 이용한 후향적 연구로, 2016년 1월~2017년 1월까지 인지기능장애를 주소로 기억장애 클리닉을 내원하여 인지기능검사를 통해 SMI나 aMCI로 진단받은 45세 이상의 성인 환자 중 주관적 수면의 질 설문지를 작성한 환자를 대상으로 하였다. 이 중 설문지 내용이 불충분한 경우, 뇌 영상검사(CT, MRI)에서 인지기능에 영향을 줄 수 있는 구조적 이상이 발견된 환자나 두부손상, 정신질환 또는 파킨슨병과 같은 신경계 질환이 동반된 경우는 수면과 인지 기능 평가에 영향을 줄 수 있어서 제외하였다. SMI 집단과 aMCI 집단을 주관적 수면의 질 평가결과에 따라, 다시 수면의 질이 좋은 군(GS)과 수면의 질이 나쁜 군(PS)으로 분류하였다(Fig. 1).

본 연구에 사용된 모든 연구 기준과 방법 및 평가는 삼성서울병원의 기관윤리심의위원회의 심의와 동의 면제 승인을 획득하였으며, 기관윤리심의위원회의 관리감독하에 시행되었다(승인번호 2020-04-074).

주관적 수면의 질모든 대상자들은 주관적 수면의 질을 평가하는 피츠버그 수면의 질 평가척도(Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI-K)를 작성하였다. PSQI는 지난 1개월간의 수면의 질과 양을 포괄적으로 평가할 수 있는 도구로 18문항 7개 하위 항목(주관적인 수면의 질, 수면 잠복기, 수면시간, 수면효율, 수면장애, 수면제 사용, 주간기능장애)으로 구성되어 있다[11]. 각 하부영역마다 0~3점으로 환산되어 총 점수는 0~21점이며 점수가 높을수록 수면의 질이 떨어지는 것으로, 5점 초과인 경우 수면의 질이 나쁜 것으로 평가한다[11]. 본 연구에서는 PSQI-K 총점이 5점 이하인 대상자는 GS군, 5점 초과면 PS군으로 분류하였다. 그 외에도 PSQI-K에서 도출된 주관적으로 평가한 잠자리에 누워있는 시간(time in bed), 수면 잠복기(sleep latency), 수면시간(total sleep time), 수면효율(sleep efficiency) 등을 추가로 분석하였다.

신경심리검사신경심리평가 도구는 한국판 간이정신상태검사(Korean-mini mental status examination, K-MMSE), 임상치매평가 척도(Clinical dementia rating, CDR)를 포함한 서울신경심리검사(Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery, SNSB)를 이용하였다[12-15]. SNSB는 다양한 인지기능을 종합적으로 평가하여 치매평가에 사용할 수 있도록 2012년 강연욱 등에 의해 국내에서 개발한 검사 총집으로, 주의집중력(digit span: forward/backward, letter cancellation), 언어능력 및 그와 관련된 기타 능력들(spontaneous speech, comprehension, repetition, reading, writing, finger naming, calculation, body part identification, Korean Boston naming test, praxis), 시공간적 지각 및 구성 능력(block design, clock drawing test, Rey complex figure test copy), 기억력(Seoul verbal learning test, Rey complex figure test memory) 및 전두엽기능(digit symbol coding, go no go test, fist edge palm test, controlled oral word association test, luria loop test, alternating hand movement, color word stroop test)에 대한 표준화된 평가 항목으로 구성되어 있다. 본 연구에서는 SNSB 각 검사의 원점수를 표준점수로 변환하여 주의집중, 전두엽 집행기능, 언어적 기억력, 시각적 기억력, 언어능력의 다섯 가지 영역별로 평균값을 계산하여 종합점수(composite score)를 계산하였고, SNSB에 사용되는 모든 신경심리검사 결과는 나이와 학력을 보정한 국내 기준을 사용하였다.

노인우울척도는 최근 2주 동안 대상자의 느낌을 조사한 척도로 Yesavage 등이 개발한 도구의 단축형을 한국인에 맞도록 수정한 한국판 노인우울척도 단축형(Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form-Korea version, GDSSF-K)을 사용하였다[16,17]. GDSSF-K는 노화의 과정과 관련이 있을 수 있는 통증, 변비 등과 같은 신체 증상을 포함하지 않고, 질문 문항을 보다 단순하고 쉽게 ‘예/아니오’로 답하게 하여 노인층에서의 우울증상을 선별하고 측정하는데 유용하게 사용할 수 있는 특성이 있다. 총 15개의 문항으로 구성되어 있으며 각 문항에 대해 우울성 응답에는 1점, 비우울성 응답에는 0점을 주며, 점수가 높을수록 우울 점수가 높음을 시사한다.

결 과SMI, aMCI 집단에서 GS군과 PS군 간 대상자의 일반적 특성 및 주관적 수면 습관 비교총 282명의 연구대상자가 등록되었으며, 이 중 제외 기준에 해당하는 36명을 뺀 246명의 환자들을 대상으로 분석을 시행하였다. 환자들의 평균 연령은 69.8±8.3(범위, 45~88)세이고, 남자 82명(33.3%), 여자 164명(66.7%)이었다. 이 중 SMI로 진단된 환자는 126명(51.2%)이었고, aMCI로 진단된 환자는 120명(48.8%)이었다. SMI 환자 중 GS군은 58명(46.0%), PS군은 68명(54.0%)으로 aMCI 환자에서의 GS군 58명(48.3%), PS군 62명(51.7%)과 비슷한 분포를 보였다(Fig. 1).

SMI 집단과 aMCI 집단에서 각각 GS군과 PS군 간 나이, 성별, 교육 년수는 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다. 평소 수면 습관 중 잠자리에 누워있는 시간은 SMI, aMCI 모두 GS군과 PS군 간의 차이가 없었으나 PS군이 GS군에 비해 수면잠복기는 길고, 수면시간은 짧았으며, 수면효율이 더 낮은 것으로 조사되었다(all p<0.001)(Table 1).

SMI, aMCI 집단에서 GS군과 PS군 간 수면의 질 비교SMI 집단과 aMCI 집단에서 GS군과 PS군 간 PSQI-K 점수를 하위 항목을 비교한 결과 SMI와 aMCI 집단 모두 7개 하위 항목(주관적 수면의 질, 수면 잠복기, 수면시간, 수면효율, 수면장애, 수면제 사용, 주간기능장애)에서 GS군이 PS군보다 유의하게 낮은 점수를 보였다(all p<0.01)(Table 2).

SMI, aMCI 집단에서 GS군과 PS군 간 신경심리검사 결과 비교K-MMSE 점수는 SMI 집단과 aMCI 집단 모두에서 GS-PS간 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다. CDR의 경우 SMI 집단에서만 PS군이 GS군보다 약간 높게 나타났으나(0.49±0.06 vs. 0.45±0.15, p=0.041), 전체 SMI 환자들의 CDR 점수는 0점(7명) 혹은 0.5점(118명)이었고, aMCI 집단에서는 1명(1점)을 제외하고 모두 0.5점이어서 수면의 질에 따른 차이가 없었다.

우울 수준은 SMI 집단에서 GS군보다 PS군이 유의하게 높게 나타났으며(3.12±3.20 vs. 5.50±4.11, p<0.001), aMCI 집단에서도 GS군보다 PS군이 유의하게 높았다(2.19±2.15 vs. 5.35±3.92, p<0.001). 따라서 SMI, aMCI 환자 집단 모두에서 수면의 질이 좋은 군보다 수면의 질이 나쁜 군이 더 우울하였다.

SNSB 검사 결과를 비교하였을 때 aMCI 집단에서만 Stroop word test 항목에서 PS군이 GS군에 비해 낮은 수행을 보였으나(111.42±2.94 vs. 109.06±8.50, p=0.043), 그 외 항목들과 종합점수에서는 SMI 집단과 aMCI 집단 모두에서 GS-PS간 객관적 인지기능의 유의한 차이는 없었다(Table 3).

고 찰수면은 성인의 건강과 삶의 질에 매우 중요한 요소이다[18,19]. 불충분한 수면은 특히 노인 인구에서 질병과 사망, 인지기능 저하와 연관이 있다고 알려져 있다[19]. 이전 논문들에 의하면 수면과 인지기능의 연관성에 관해서는 다양한 연구 결과들이 있는데 쥐를 대상으로 한 동물 실험 연구에서 수면-각성 주기와 Orexin이 AD의 주요 인자로 알려져 있는 물질인 베타 아밀로이드(β-amyloid) 축적에 영향을 준다는 결과를 발표하였으며[20], Actigraphy를 이용한 객관적인 수면 지표를 이용한 연구에서 수면분절은 AD와 인지기능 저하와 연관이 있다고 보고하였다[21]. 수면은 기억 형성에 중요한 해마의 구조적 가소성을 촉진시키고 각성, 인지, 기분에 관한 뇌의 기능에 영향을 준다[22,23]. 또한 자기보고형 설문지를 이용하여 수면과 β-amyloid 축적의 연관성을 연구한 논문에서 수면의 질이 나쁠수록 β-amyloid 부담이 커진다는 결과도 있어 주관적 수면의 질과 인지기능 사이의 연관 관계가 있을 것이라고 유추해 볼 수 있다[24]. 하지만, 주관적 수면의 질과 인지기능의 관계에 대해서는 연구마다 결과가 일관되지 않았다. Nebes 등은 건강한 노인에서 수면의 질이 집행기능, 주의력, 전반적인 인지기능과 연관이 있다고 발표하였으며[25], Schmutte 등은 입면 장애가 장기 기억력, 시공간 기능에 나쁜 영향을 준다는 결과를 발표하였다[26]. 또한 주관적 수면의 질이 처리속도, 집행기능, 작업기억, 언어적 유창성, 문제해결력 등과 연관이 있다는 다양한 연구들이 있다[25,27,28]. 반면에 다른 연구에서는 Trail making test A 이외의 집행기능, 기억력, 언어적 유창성, 지능 검사 등 다른 인지 평가 항목에서는 GS-PS간 차이가 없는 결과를 발표하였고[29], GS-PS간 객관적 인지기능은 차이가 없었으나 우울과 수면의 질, 주관적 기억력 저하가 연관성 있다는 결과도 있었다[10]. MCI 환자와 정상군의 수면다원검사(polysomnography, PSG) 결과를 비교한 연구에서도 두 그룹간 수면시간, 수면단계, 각성지수 등을 포함한 모든 수면 지표의 차이가 관찰되지 않았다[30].

선행 연구에서 일반 인구 집단에서 수면의 질이 나쁜 군은 10~48%로 보고되었는데, 치매 환자가 포함된 기억장애 클리닉을 방문한 환자를 대상으로 한 이전 연구에서는 47%에서 수면의 질이 나쁜 것으로 보고하였으며[8,31], SMI, MCI와 치매 환자에서의 불면증을 연구한 국내 논문에서는 불면증의 유병률이 각각 23.2%, 19.6%, 31.0%로 나타났다. SMI 환자들을 대상으로 한 국내 연구에서는 PS가 전체의 54.5%로 관찰되었는데[10], 본 연구 대상자들에서는 수면의 질이 나쁜 PS군이 전체의 52.8%였고, SMI 집단 중 54.0%, aMCI 집단 중 51.7%로 이전 연구들에 비해 비슷하거나 다소 높은 비율을 보였다. SMI, aMCI 두 집단에서 GS-PS간 PSQI 하위 항목을 비교한 결과 PSQI 총점 뿐만 아니라 7가지 하위 항목에서도 모두 유의한 차이가 관찰되었다.

신경심리평가 결과 중 CDR은 SMI 집단에서만 PS군이 GS군에 비해 높은 점수를 보였는데, 이는 인지기능이 정상이면서 수면의 질이 나쁜 환자들이 주관적으로 기억력 저하 호소를 많이 한다는 이전 연구들과 공통점을 가진다[3,32]. aMCI 집단에서는 대부분의 환자들의 CDR 점수가 0.5점이었기 때문에 CDR 점수로는 인지기능 차이를 평가할 수 없었다.

본 연구 대상자들은 SMI 환자 집단과 aMCI 집단 모두에서 GS군보다 PS군이 더 우울한 것으로 나타났는데 이는 이전 연구들에서 알려진 바와 같은 맥락으로 기존 연구들에 따르면 수면과 우울은 서로 영향을 주고 받는 양방향성(bi-directional)의 관계를 가진다고 알려져 있다[22,33]. PSQI를 이용하여 수면의 질과 정신 건강과의 관련성을 연구한 논문에서는 PSQI 하위 항목들이 우울, 불안, 스트레스와 유의한 연관성이 관찰되었고[34], 우울감 지수인 Patient Health Questionnaire-9와 PSQI를 분석한 연구에서도 두 점수가 양적 상관관계를 보였다[31].

여러 연구에서 수면 문제가 있을 때 인지 저하와 치매 발병 위험이 증가된다고 보고하였으며, AD의 약 15%는 수면 문제로 인한 것일 수 있다[21,35-37]. 그러나 수면의 질에 따른 인지기능의 차이를 보고한 이전 연구들과 달리 본 연구 대상자들은 aMCI 집단의 Stroop word test 항목에서만 PS군이 GS군에 비해 약간 낮은 점수를 보인 것 이외에, 다른 항목들과 종합점수에서는 SMI, aMCI 집단 모두 GS-PS 양 군간의 차이가 관찰되지 않았다. 따라서, 인지기능이 정상인 SMI 집단에서는 수면에 질에 따른 객관적 인지기능의 차이는 없었으나 aMCI 집단에서는 나쁜 수면의 질이 전두엽, 집행기능에 일부 부정적인 영향이 있을 수 있다는 결론을 얻을 수 있었고, 이전 연구들에서 수면의 질이 나쁜 군에서 인지기능 검사상 집행기능 저하[25,28,29], 처리 속도 저하[27], 기억력 저하[26,32]가 보고된 결과들과는 일치하지 않았다. 본 연구에서 PS군이 SNSB상 GS군과 비교하여 전반적 인지기능에 뚜렷한 차이가 없었던 이유에 대해서는 첫째로 본 연구에서 상대적으로 여성 대상자가 남성보다 많이 포함되어 있어 Stroop color test에서 여성이 남성보다 좋은 수행을 보였다는 일부 연구를 참고할 때 PS군의 전두엽, 집행기능의 낮은 수행이 상대적으로 높이 평가되었을 가능성도 있으며[38], 둘째로는 PS군의 나쁜 수면의 질에 대한 보상기전으로 생리적 각성이 증가되어 객관적 평가에서 상대적으로 좋은 수행을 보였다는 가설도 고려해 볼 수 있다[39,40].

본 연구의 제한점은 노인 인구에서 흔히 동반될 수 있는 기저질환과 복용 약물이 수면에 미치는 영향을 배제하지 못 했다는 점이다. 또한 환자들의 수면에 대한 평가에 PSG나 Actigraphy 등의 객관적인 도구들을 이용하지 않고 자기보고형 설문지인 PSQI로 수면의 질을 평가했다는 점도 제한점으로 들 수 있다. 지난 1개월 간의 수면의 질을 평가하는 것으로 장기적인 수면상태를 정확히 반영한다고 보기 어려우며 기억력 저하를 호소하는 인지기능 저하 환자들은 실제 수면 문제가 있음에도 자신의 문제를 잘 인지하지 못하거나 과대 평가할 가능성이 있다[41]. PSG 결과가 없어 인지기능 장애를 초래할 수 있는 수면호흡장애 유무도 알 수 없었다[42]. 객관적 도구인 Actigraphy를 이용한 다른 연구에서는 입면 후 각성시간(wakefulness after sleep onset)이 인지기능 저하와 연관이 있었다[43,44]. 그러나 PSQI로 평가한 수면 습관은 PSG 지표들과 근본적으로 다르며 PSQI가 비수면장애로부터 수면장애를 구별하는데 유용하게 사용되므로 나름대로 의의가 있다[45,46]. 추가적으로 기억력 저하를 호소하는 환자들을 추적 관찰하여 주관적 수면의 질이 향후 인지기능에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대해서 후속 연구가 필요할 것으로 보인다.

본 연구의 목적은 기억력 저하를 호소하는 환자들을 SMI, aMCI 집단으로 구분하고 각각 GS-PS로 분류하여 이들의 특성을 비교하는 것으로 기존 연구들과는 다르게 인지 기능이 정상인 SMI 집단과 경미한 인지 기능 저하가 있는 aMCI 집단을 함께 비교하여 주관적 수면의 질에 따른 특성을 조사하였다는 점에서 의의가 있다. 본 연구 결과에 따르면 정상 인지기능을 가진 환자들에서 나쁜 수면의 질이 주관적 기억력 저하 호소와 연관이 있을 가능성이 있으며 경미한 인지저하가 있는 환자들에게는 나쁜 수면의 질이 일부 전두엽, 집행기능에 부정적 영향을 줄 수 있다. 또한, 주관적으로 인지 저하를 호소하는 환자들이 추후 치매로 진행될 가능성이 있기 때문에 임상에서 이러한 환자들을 진료할 때 PSQI를 이용하여 수면의 질을 평가한다면 중재 가능한 수면 장애에 대한 개입이 가능할 것이고 인지기능이 정상인 SMI 환자들이 나쁜 수면의 질로 인하여 기억력 저하를 호소하는 것을 설명 가능하며, 수면장애에 의해 우울 증상을 호소하는 것인지도 확인하는데 도움이 될 것으로 보인다[47].

AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported by Samsung Biomedical Research Institute grant (OTC1190671).

We thank Duk L. Na, Sang Won Seo, Hee Jin Kim for their help in data collection.

NotesAuthor Contributions

Conceptualization: Eun Yeon Joo, Su Jung Choi, Hwa Reung Lee. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: Hwa Reung Lee, Su Jung Choi. Investigation: Hwa Reung Lee, Juhee Chin. Methodology: Su Jung Choi, Eun Yeon Joo, Hwa Reung Lee. Supervision: Su Jung Choi, Eun Yeon Joo. Writing—original draft: Hwa Reung Lee, Su Jung Choi. Writing—review & editing: Su Jung Choi, Eun Yeon Joo

Figure 1.Enrollment Log of the Study. We enrolled 246 patients with memory impairment (126 with SMI and 120 with aMCI), and patients were classified as good sleepers (GS) or poor sleepers (PS) based on the PSQI-K cutoff point of 5. SMI: subjective memory impairment, aMCI: amnestic mild cognitive impairment, PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Table 1.Demographic data and habitual sleep habit according to sleep quality in SMI and aMCI patients (n=246)

Table 2.PSQI components according to sleep quality in SMI and aMCI patients (n=246) Table 3.Comparison of neuropsychological data according to sleep quality in SMI and aMCI patients (n=246) Values are expressed as mean±standard deviation. SMI: subjective memory impairment, aMCI: amnestic mild cognitive impairment, MMSE: Korean-Mini Mental State Examination, CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating, GDSSF-K: Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form-Korea version, COWAT: Controlled Oral Word Association Test, TMT: Train Making Test, SVLT: Seoul Verbal Learning Test, RCFT: Rey Complex Figure Test, GS: good sleeper, PS: poor sleeper REFERENCES1. Statistics Korea. Population Projections for Korea (2017-2067) [online]. [cited 2019 June 1]. URL: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1BPA003&language=en&conn_path=I3.

2. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183-194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x.

3. Tsapanou A, Vlachos GS, Cosentino S, et al. Sleep and subjective cognitive decline in cognitively healthy elderly: results from two cohorts. J Sleep Res 2019;28:e12759. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12759.

4. Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006;367:1262-1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5.

5. Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:844-852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001.

6. Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:1924-1938. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.4668.

7. Suh SW, Han JW, Lee JR, et al. Sleep and cognitive decline: a prospective nondemented elderly cohort study. Ann Neurol 2018;83:472-482. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25166.

8. Hinz A, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, et al. Sleep quality in the general population: psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, derived from a German community sample of 9284 people. Sleep Med 2017;30:57-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.03.008.

9. Adam AM, Potvin O, Callahan BL, et al. Subjective sleep quality in non-demented older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;29:970-977. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4087.

10. Kang SH, Yoon IY, Lee SD, et al. Subjective memory complaints in an elderly population with poor sleep quality. Aging Ment Health 2017;21:532-536. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1124839.

11. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4.

12. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc 1997;15:300-308.

13. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566-572. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.140.6.566.

14. Choi SH, Na DL, Lee BH, et al. Estimating the validity of the Korean version of expanded clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale. J Korean Neurol Assoc 2001;19:585-591.

15. Kang Y, Jahng S, Na DL. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery. (SNSB-II): professional manual. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting, 2012.

16. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165-173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09.

17. Kee BS. A preliminary study for the standardization of geriatric depression scale short form-Korea version. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1996;35:298-307.

18. Kim D, Chang HJ, Lee W, et al. Circadian rhythm, sleep quality, and health-related quality of life in Korean middle adults. J Sleep Med 2020;17:66-72. https://doi.org/10.13078/jsm.200005.

19. Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep 1995;18:425-432. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/18.6.425.

20. Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, et al. Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 2009;326:1005-1007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180962.

21. Lim AS, Kowgier M, Yu L, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep 2013;36:1027-1032. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2802.

22. Raven F, Van der Zee EA, Meerlo P, Havekes R. The role of sleep in regulating structural plasticity and synaptic strength: implications for memory and cognitive function. Sleep Med Rev 2018;39:3-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.05.002.

23. Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:114-126. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2762.

24. Spira AP, Gamaldo AA, An Y, et al. Self-reported sleep and β-amyloid deposition in community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:1537-1543. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4258.

25. Nebes RD, Buysse DJ, Halligan EM, Houck PR, Monk TH. Self-reported sleep quality predicts poor cognitive performance in healthy older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64:180-187. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbn037.

26. Schmutte T, Harris S, Levin R, Zweig R, Katz M, Lipton R. The relation between cognitive functioning and self-reported sleep complaints in nondemented older adults: results from the Bronx aging study. Behav Sleep Med 2007;5:39-56. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15402010bsm0501_3.

27. Bastien CH, Fortier-Brochu E, Rioux I, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Morin CM. Cognitive performance and sleep quality in the elderly suffering from chronic insomnia. Relationship between objective and subjective measures. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:39-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00544-5.

28. Waters F, Bucks RS. Neuropsychological effects of sleep loss: implication for neuropsychologists. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2011;17:571-586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711000610.

29. Saint Martin M, Sforza E, Barthélémy JC, Thomas-Anterion C, Roche F. Does subjective sleep affect cognitive function in healthy elderly subjects? The Proof cohort. Sleep Med 2012;13:1146-1152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2012.06.021.

30. Kim SJ, Lee JH, Lee DY, Jhoo JH, Woo JI. Neurocognitive dysfunction associated with sleep quality and sleep apnea in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;19:374-381. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e9b976.

31. Hancock P, Larner AJ. Diagnostic utility of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in memory clinics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:1237-1241. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2251.

32. Gamaldo AA, Wright RS, Aiken-Morgan AT, Allaire JC, Thorpe RJ Jr, Whitfield KE. The association between subjective memory complaints and sleep within older African American adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2019;74:202-211. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx069.

33. Riemann D, Berger M, Voderholzer U. Sleep and depression--results from psychobiological studies: an overview. Biol Psychol 2001;57:67-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00090-4.

34. Del Rio João KA, de Jesus SN, Carmo C, Pinto P. Sleep quality components and mental health: study with a non-clinical population. Psychiatry Res 2018;269:244-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.020.

35. Bubu OM, Brannick M, Mortimer J, et al. Sleep, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2017;40:zsw032. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw032.

36. Xu W, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of allcause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020;91:236-244. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-321896.

37. Wardle-Pinkston S, Slavish DC, Taylor DJ. Insomnia and cognitive performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2019;48:101205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.07.008.

38. Jensen AR, Rohwer WD Jr. The Stroop color-word test: a review. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1966;25:36-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6918(66)90004-7.

39. Orff HJ, Drummond SP, Nowakowski S, Perils ML. Discrepancy between subjective symptomatology and objective neuropsychological performance in insomnia. Sleep 2007;30:1205-1211. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.9.1205.

40. Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, Kupfer DJ. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:2126-2128. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126.

41. Westerberg CE, Lundgren EM, Florczak SM, et al. Sleep influences the severity of memory disruption in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: results from sleep self-assessment and continuous activity monitoring. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:325-333. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181e30846.

42. Fulda S, Schulz H. Cognitive dysfunction in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev 2001;5:423-445. https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2001.0157.

43. Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the MrOS sleep study. Sleep 2011;34:1347-1356. https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1276.

44. Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Poor sleep is associated with impaired cognitive function in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:405-410. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.4.405.

45. Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4:563-571. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.27351.

46. Germain A, Moul DE, Franzen PL, et al. Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for late-life insomnia: preliminary findings. J Clin Sleep Med 2006;2:403-406. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.26654.

47. Gifford KA, Liu D, Lu Z, et al. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:319-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.007.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||